Research

Assessment of patients with NCC (Neurocysticercosis) in the North Indian population on the questionnaire based approach and its significance

Assessment of patients with NCC (Neurocysticercosis) in the North Indian population on the questionnaire based approach and its significance

Niraj Kumar Srivastavaa,* Arpan Mitra,a Nidhi Chandraa, Neha Srivastava,a Arvind Kumar Dasa, Nikhil Pandeya, Viturv Tripathia and Ankur Viveka.

Dr. Niraj Kumar Srivastava,Postdoctoral Researcher,Department of Neurology,IMS, BHU ,Varanasi-221005(UP), INDIA

E-mail: nirajsuprabhat@gmail.com

Abstract

NCC (Neurocysticercosis) is an extensive parasitic disease of the human nervous system and caused by the infection of Taenia solium. This is indeed a significant social health issue in the worldwide population. Assessment of patients with NCC using a questionnaire-based approach can provide valuable insights of the disease, specifically symptomatology. This enables a comprehensive understanding of the patient's clinical status. All patients (N=50) experienced seizures. The mean duration was 3.78 ± 4.54 years. Focal seizures were found 84% (42/50) of cases. Generalized seizures were found 16% (8/50) of cases. The mean seizure frequency was 1.90 ± 1.57 (presumably per year, but not specified) for the 22 cases mentioned. All patients (N=50) experienced seizures. The mean duration was 3.78 ± 4.54 years. Focal seizures were found 84% (42/50) of cases. Generalized seizures were found 16% (8/50) of cases. The mean seizure frequency was 1.90 ± 1.57 (presumably per year, but not specified) for the 22 cases mentioned. Headache was found in 80% (40/50) of cases, dizziness was in 96% (48/50) of cases and post-seizure vomiting was observed in 24% (12/50) of cases. Vision abnormality was observed in 4% (2/50) of cases, while 96% (48/50) showed no vision abnormalities. Family History of Seizures was found positive in 20% (10/50) of cases. History of head trauma/injury was found positive in 12% (6/50) of cases. This profile shows that focal seizures are more common than generalized seizures among patients with NCC, and that dizziness, headaches, and post-seizure vomiting are frequently reported symptoms. Additionally, a family history of seizures and prior head trauma may be relevant risk factors for some of the patients. This profile shows that focal seizures are more common than generalized seizures among patients with NCC, and that dizziness, headaches, and post-seizure vomiting are frequently reported symptoms. Additionally, a family history of seizures and prior head trauma may be relevant risk factors for some of the patients. This study reflects the assessment of the clinical profile of patients with NCC in the North Indian population and its significance. Questionnaires based outcomes of patients with NCC of the present study are contributed to evaluate the effectiveness of new interventions or combined therapeutic approaches, including Ayurveda, Yoga, and dietary modifications.

Introduction

Neurocysticercosis (NCC) indeed poses a significant public health challenge, particularly in developing countries where sanitation and control measures for Taenia solium are often inadequate. This parasitic infection of the CNS, caused by the ingestion of T. solium eggs, is a leading cause of acquired epileptic seizures, making up a substantial percentage of cases, ranging from 26.3% to 53.8% in developing regions such as India and Latin America [1-8]. However, NCC is not confined to these endemic areas. The global movement of people due to immigration, travel, and other factors has facilitated the spread of NCC to more developed nations with well-organized healthcare systems. Individuals from endemic regions may either carry the infection themselves or act as transporters of T. solium, leading to the disease's emergence as a recognized health concern even in countries with advanced clinical setups. This underscores the importance of global health surveillance, proper diagnostic measures, and international cooperation to manage and prevent the spread of NCC beyond its traditional boundaries [1-8].

A research questionnaire is a structured data collection tool comprising a set of questions designed to gather specific information from respondents. It aims to understand their knowledge, opinions, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. The design of a questionnaire is often informed by the research objectives, hypotheses, and underlying theoretical framework. Questionnaires are frequently associated with a positivist philosophy, which emphasizes objective measurement and the quantification of variables, typical of the natural sciences. This alignment suggests that questionnaires are used to test hypotheses and establish patterns that can be generalized to larger populations. In research studies, questionnaires can serve as a primary data collection method, particularly in quantitative research [9-12]. They are also utilized in mixed-method studies, where they complement qualitative techniques such as interviews or focus groups, providing a more comprehensive view of the research problem. The development and use of questionnaires have indeed become a significant focus in research, especially in the healthcare area. This tendency reflects a growing recognition of the importance of patient-reported outcomes and patient perspectives on both clinical and non-clinical tendency of care. Questionnaires are invaluable tools for capturing subjective data, such as patients' perceptions of their health status, satisfaction with care, adherence to treatment, and quality of life. Absolutely the rigorous scientific standards are crucial for ensuring that research findings are credible, reproducible, and valuable. These standards help ensure that research contributes to the body of knowledge in a meaningful and reliable way [9-13].

In the present study, we are providing the systematic, well organized and comprehensive questionnaire based outcomes of patients with NCC of the North Indian population. These are no such extensive reports on the NCC patients. Questionnaires based outcomes of patients with NCC of the present study are contributed to evaluate the effectiveness of new interventions or combined therapeutic approaches, including Ayurveda, Yoga, and dietary modifications.

Key words: Epilepsy, Neurocysticercosis, NCC, Taenia solium cysticerci, Questionnaires based assessment.

Abbreviations: NCC: Neurocysticercosis; CT: Computer Tomography; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; CSF: Cerebrospinal Fluid; EEG: Electroencephalography.

Material and Methods

Study design and research population

The present study was performed in qualitative and the quantitative manners, and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Institute of Medical Sciences (IMS), Banaras Hindu University (BHU), Varanasi (UP), India. The approval committee number is Dean/2023/EC/6806.

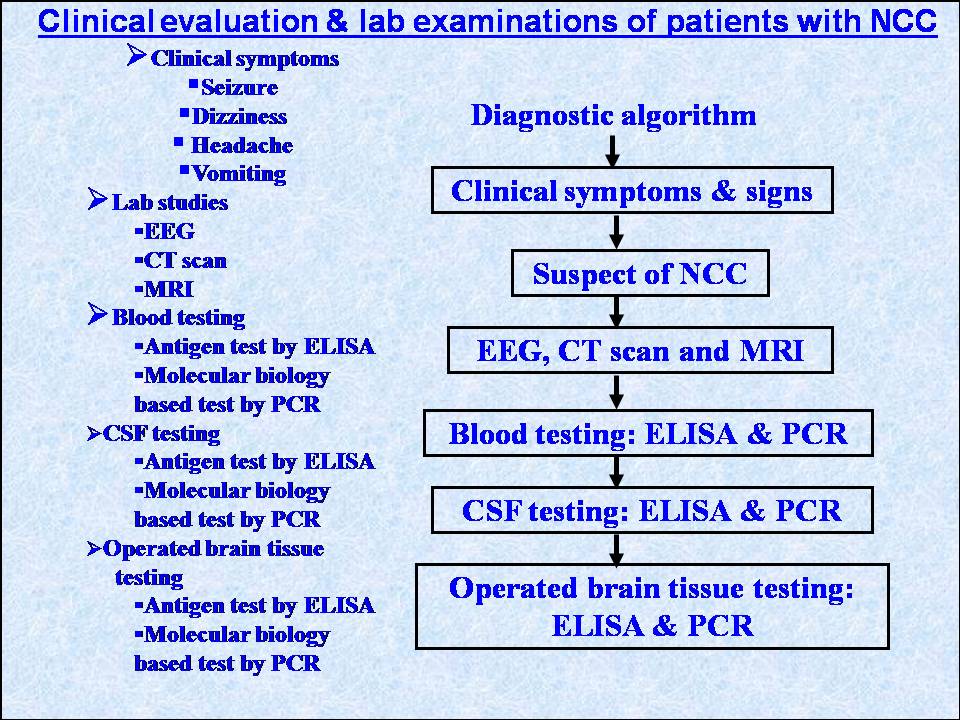

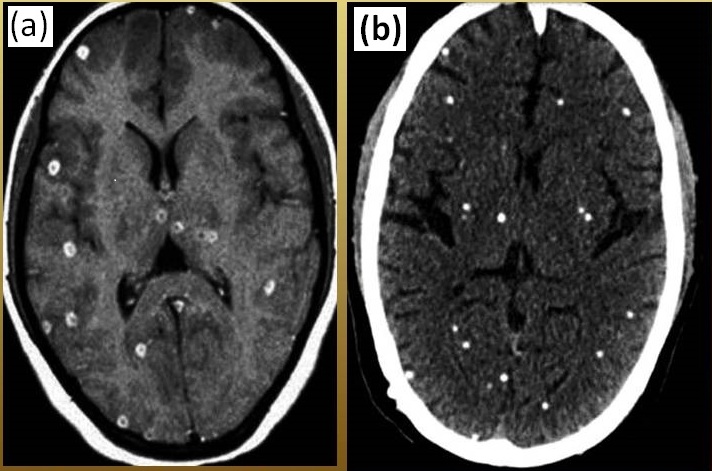

All the patients (N=50), who participated in the present study, were enrolled in the OPD of the department of neurology, IMS, BHU. Figure-1 represented the entire overview of the diagnosis of patients with NCC. All the diagnostically confirmed cases (MRI /CT scan based imaging) of NCC were included in the present study (Figure-2).

Questionnaire-based approach

Assessing patients with neurocysticercosis (NCC) using a questionnaire-based approach can be a valuable tool in both clinical practice and research settings. This method allows for a systematic evaluation of symptoms, quality of life, treatment response, and other patient-reported outcomes, which can help tailor individualized care and track disease progression. Here, we are presenting an overview of such assessments:

Personal Assessment

Age, sex, physical challenges, employment, marital status, education, dietary pattern and economical ground of all the NCC patients were assessed.

Symptom Assessment

-

- Seizure Frequency and Severity: Since seizures are the most common manifestation of NCC, questionnaires often include detailed queries about the type, frequency, duration, and impact of seizures on daily life.

- Headache and Neurological Symptoms: Assessing the presence, frequency, and severity of headaches, as well as other neurological symptoms, such as dizziness, and visual disturbances.

Data analysis

All the collected data of NCC patients were represented in the form of number/percentage/ mean value. The percentage/ mean value compared by Student‘t’ test for independent groups. The p value b 0.05 was considered significant. The data management and analysis were carried out using statistical software SPSS version 15.0.

Results

Personal outcomes

The NCC patients, who participated in the present study, were between 8 and 63 years of age with an average value of 22.80 ±12.21 years. Entire of these, 48% (24/50) of the patients were female and the 52% (26/50) were male. The significant difference was not observed (p>0.05). Physical challenges were observed in 4 % (2/50) case of NCC. On the ground of employment, 40% (20/50) of the patients were student, 18 % (9/50) were housewives, 10% (5/50) were employed and 32% (16/50) were unemployed. On the ground of marital status, 48% (24/50) patients were married and 52% (26/50) were unmarried. The significant difference was not observed (p>0.05). On the educational background, 90% (45/50) of the NCC patients were educated and 10% (5/50) were illiterate. The significant difference was observed (p<0.05). On the ground of dietary pattern, 84% (42/50) patients were taken the non-vegetarian diet and 16% (8/50) patients were consumed the vegetarian diet. The significant difference was observed (p<0.05). Economical ground showed the 88% (44/50) patients were middle class and 12% (6/50) patients were belonged to the lower middle class. The significant difference was observed (p<0.05).

Symptom outcomes

All the patients (N=50) with NCC showed the symptoms of seizure. The mean value of the duration of the disease was 3.78 +4.54 years. In all these, 84% (42/50) cases were represented the focal seizure and 16 % (18/50) represented the generalized seizure. The significant difference was observed (p<0.05). The mean value of the seizure frequency was 1.90 +1.57 for all the twenty two cases. Other symptoms, headache was represented by 80% cases (40/50), dizziness was represented by 96% cases (48/50) and vomiting after post-seizure was represented by 24% cases (12/50). Vision abnormality was found only 4% (2/50) cases and 96% (48/50) cases did not show it. The significant difference was observed (p<0.05). Family history of seizure was found positive for 20% (10/50) cases. The significant difference was observed (p<0.05). History of head trauma/ injury was found positive for 12% (6/50) cases.

Discussion

The present study aimed to develop a questionnaire to assess the clinical profiles of patients with NCC. The initial draft of the current questionnaire was developed based on a qualitative study. Here, fifty (N = 50) patients with NCC items were included. All these patients were belonged to the eastern UP and western Bihar (UP and Bihar are two states of India).

The age range from 8 to 63 years with an average age of 22.8 years, indicates a broad demographic in the study. This could reflect variability in how NCC affects different age groups and may provide insights into age-related differences in symptoms, treatment responses, or disease progression. The observation of a bimodal distribution of epilepsy incidence, including cases related to neurocysticercosis (NCC), is well-supported to our findings. Hauser et al. found that the incidence of epilepsy, including NCC, peaks during the first year of life and again after the age of 74. Similarly, Mani et al. and Banerjee et al. have identified a bimodal pattern, with peaks in early childhood and again in the 70s and 80s. On the basis of the outcome of one study, it was found that the range of the age of NCC patients was 23 to 50 years. This outcome also supported our findings [14-17].

Entire of these, 48% (24/50) of the patients were female and the 52% (26/50) were male. There is no significant difference observed between the numbers of male vs. female patients with NCC. This finding is also supported by the previous studies [14-17].

Based on the employment status of the 50 patients with neurocysticercosis (NCC), students are 40% (20 out of 50), housewives are18% (9 out of 50),employed people are10% (5 out of 50) and unemployed are 32% (16 out of 50).This data provides a snapshot of the demographic distribution of NCC patients concerning the employment status. It shows that a significant proportion is students, while the employed group is relatively smaller. There is not much information available about the employment status of the patients with NCC.

Outcomes of the present study, 48% of the patients with neurocysticercosis (NCC) were married, which accounts for 24 out of 50 patients. Meanwhile, 52% were unmarried, making up 26 out of the 50 patients. This suggests a fairly balanced distribution of marital status among the NCC patients, with a slight predominance of unmarried individuals. There is not much information available about the marital status of the patients with NCC.

The educational background of NCC patients, where 90% were educated and only 10% were illiterate, is indeed significant in several contexts. Educated individuals might have better access to information about hygiene, sanitation, and preventive measures against parasitic infections like Taenia solium, which causes neurocysticercosis. Awareness campaigns and educational materials can be more effectively communicated to those who are literate. Educated patients are generally more likely to understand their diagnosis and treatment plan, which can enhance medication adherence. They may better comprehend the importance of completing a course of anti-parasitic drugs, managing side effects, and following up with medical professionals. The higher proportion of educated patients could suggest that those with some level of education may seek medical help more promptly, recognize symptoms earlier, or have more access to healthcare facilities. This data could also reflect socioeconomic factors, as education often correlates with better living conditions and access to healthcare resources. It's important to consider how these factors might influence both the prevalence and management of NCC [18-20].

Significant majority of patients with neurocysticercosis (NCC) in this study were consuming a non-vegetarian diet. 84% of patients (42 out of 50) were on the non-vegetarian diet and 16% of patients (8 out of 50) on the vegetarian diet. This distribution could provide some insights into the dietary patterns associated with NCC cases in the studied population. In many regions, consuming undercooked or contaminated pork is a known risk factor for developing NCC, as the disease is caused by the larval stage of Taenia solium, the pork tapeworm [7, 21-24].

The socioeconomic background of neurocysticercosis (NCC) patients is quite insightful. With 88% of the patients belonging to the middle class and 12% to the lower middle class, this distribution suggests some interesting points. Middle-class individuals might have better access to healthcare services and awareness about conditions like NCC compared to those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. This could mean that middle-class patients are more likely to seek diagnosis and treatment. Being in the middle class may offer some financial stability, allowing patients to afford the necessary medication and treatment for NCC, which can involve costly imaging studies (like CT or MRI scans), anti-parasitic drugs, corticosteroids, and anticonvulsants. The finding also highlights the potential role of education and awareness in managing NCC. Middle-class families might have more access to health education and preventive measures (like proper sanitation and hygiene) that reduce the risk of NCC. However, despite this, the high prevalence of NCC in this group could indicate gaps in public health education or the persistence of risk factors such as poor food and water quality. There might be different health-seeking behaviors among socioeconomic groups. Middle-class individuals may be more proactive about getting treatment, whereas those from lower socioeconomic groups might delay seeking care due to financial constraints or lack of awareness. This socioeconomic pattern emphasizes the need for targeted public health strategies to improve awareness, prevention, and management of NCC across different economic backgrounds, especially for the lower middle class or those with limited access to healthcare [23, 25-27].

In the context of seizure pattern, the outcome of the present study indicates that among 50 cases of NCC, 42 cases (84%) presented with focal seizures, while the remaining 8 cases (16%) presented with generalized seizures. This distribution suggests that focal seizures are significantly more common in patients with NCC compared to generalized seizures. This could be reflective of the localization of cysts in the brain, which often affects specific areas leading to focal seizures [28-30].

The present study provides the clinical presentation and symptomatology in patients with neurocysticercosis (NCC).The mean seizure frequency among the 22 NCC cases was 1.90 with a standard deviation of ±1.57. This indicates that on average, patients experienced approximately 1 to 2 seizures, but the frequency varied widely among individuals. 80% of the cases (40 out of 50) experienced headaches, making it a common symptom among the NCC patients. 96% of the cases (48 out of 50) reported dizziness, suggesting it is one of the most prevalent symptoms in this group. 24% of the cases (12 out of 50) experienced vomiting after a seizure, indicating that while not as common as dizziness or headaches, post-seizure vomiting still affected a significant minority of patients. This study underscores the varied and often severe symptoms experienced by NCC patients, with a particularly high prevalence of dizziness and headaches [1-3, 31-32].

The present study reflects the prevalence of certain symptoms and risk factors among 50 cases of NCC. Vomiting post-seizure was observed in 24% of cases (12 out of 50), vision abnormalities were present in 4% of cases (2 out of 50) and absent in 96% of cases (48 out of 50).Family history of seizures was positive in 20% of cases (10 out of 50) and history of head trauma/injury was positive in 12% of cases (6 out of 50).These findings may help in understanding the prevalence of associated symptoms and risk factors in patients with NCC. Vision abnormalities were also reported in patients with NCC and also observed in the present study [33]. Report about the positive family history of seizure was only available in the cases of epilepsy [34], but this is not mentioned in NCC cases. The unique findings of our study were vomiting post-seizure, positive family history and history of head trauma/injury.

This study performed the assessment of the clinical profile of patients with NCC in the North Indian population and evaluated the effectiveness of new interventions or combined therapeutic approaches. By using questionnaires, the study gathers outcomes to understand how integrated approaches, such as Ayurveda, Yoga, and dietary modifications affect the health and well-being of NCC patients. The significance of this study lies in its focus on the potential benefits of these holistic methods, particularly in managing symptoms, reducing side effects, and improving quality of life. The findings could provide valuable insights into alternative or complementary strategies for managing NCC beyond conventional allopathic treatments, potentially leading to more personalized and comprehensive care plans.

Funding

This study did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Consent for publication

The patient provided written informed consent for the publication of this report and the accompanying images.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgments

The authors pay sincere thanks to patients, who were involved and gave her consent for the utilization of the clinical reports and images.

References

1. Garcia, Hector H et al. “Clinical symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of neurocysticercosis.” The Lancet. Neurology vol. 13,12 (2014): 1202-15. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70094-8

2. Del Brutto, Oscar H. “Neurocysticercosis.” The Neurohospitalist vol. 4,4 (2014): 205-12. doi:10.1177/1941874414533351

3. Michelet, L., Fleury, A., Sciutto, E., et al. Human neurocysticercosis: comparison of different diagnostic tests using cerebrospinal fluid [published correction appears in J Clin Microbiol. 2012 ;50(1):212]. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(1):195-200. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01554-10

4. Singh, Gagandeep et al. “From seizures to epilepsy and its substrates: neurocysticercosis.” Epilepsia vol. 54,5 (2013): 783-92. doi:10.1111/epi.12159

5. Garcia, Hector H et al. “Taenia solium Cysticercosis and Its Impact in Neurological Disease.” Clinical microbiology reviews vol. 33,3 e00085-19. 27 May. 2020, doi:10.1128/CMR.00085-19

6. Coyle, Christina M, and Herbert B Tanowitz. “Diagnosis and treatment of neurocysticercosis.” Interdisciplinary perspectives on infectious diseases vol. 2009 (2009): 180742. doi:10.1155/2009/180742

7. Prasad, Kashi Nath et al. “Human cysticercosis and Indian scenario: a review.” Journal of biosciences vol. 33,4 (2008): 571-82. doi:10.1007/s12038-008-0075-y

8. Del Brutto, Oscar H. “Neurocysticercosis: a review.” TheScientificWorldJournal vol. 2012 (2012): 159821. doi:10.1100/2012/159821

9. Aaronson, N K et al. “The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute vol. 85,5 (1993): 365-76. doi:10.1093/jnci/85.5.365

10. Boynton, Petra M, and Trisha Greenhalgh. “Selecting, designing, and developing your questionnaire.” BMJ (Clinical research ed.) vol. 328,7451 (2004): 1312-5. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7451.1312

11. Boynton, Petra M. “Administering, analysing, and reporting your questionnaire.” BMJ (Clinical research ed.) vol. 328,7452 (2004): 1372-5. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7452.1372

12. Ranganathan, Priya, and Carlo Caduff. “Designing and validating a research questionnaire - Part 1.” Perspectives in clinical research vol. 14,3 (2023): 152-155. doi:10.4103/picr.picr_140_23

Abstract

NCC (Neurocysticercosis) is an extensive parasitic disease of the human nervous system and caused by the infection of Taenia solium. This is indeed a significant social health issue in the worldwide population. Assessment of patients with NCC using a questionnaire-based approach can provide valuable insights of the disease, specifically symptomatology. This enables a comprehensive understanding of the patient's clinical status. All patients (N=50) experienced seizures. The mean duration was 3.78 ± 4.54 years. Focal seizures were found 84% (42/50) of cases. Generalized seizures were found 16% (8/50) of cases. The mean seizure frequency was 1.90 ± 1.57 (presumably per year, but not specified) for the 22 cases mentioned. All patients (N=50) experienced seizures. The mean duration was 3.78 ± 4.54 years. Focal seizures were found 84% (42/50) of cases. Generalized seizures were found 16% (8/50) of cases. The mean seizure frequency was 1.90 ± 1.57 (presumably per year, but not specified) for the 22 cases mentioned. Headache was found in 80% (40/50) of cases, dizziness was in 96% (48/50) of cases and post-seizure vomiting was observed in 24% (12/50) of cases. Vision abnormality was observed in 4% (2/50) of cases, while 96% (48/50) showed no vision abnormalities. Family History of Seizures was found positive in 20% (10/50) of cases. History of head trauma/injury was found positive in 12% (6/50) of cases. This profile shows that focal seizures are more common than generalized seizures among patients with NCC, and that dizziness, headaches, and post-seizure vomiting are frequently reported symptoms. Additionally, a family history of seizures and prior head trauma may be relevant risk factors for some of the patients. This profile shows that focal seizures are more common than generalized seizures among patients with NCC, and that dizziness, headaches, and post-seizure vomiting are frequently reported symptoms. Additionally, a family history of seizures and prior head trauma may be relevant risk factors for some of the patients. This study reflects the assessment of the clinical profile of patients with NCC in the North Indian population and its significance. Questionnaires based outcomes of patients with NCC of the present study are contributed to evaluate the effectiveness of new interventions or combined therapeutic approaches, including Ayurveda, Yoga, and dietary modifications.

Introduction

Neurocysticercosis (NCC) indeed poses a significant public health challenge, particularly in developing countries where sanitation and control measures for Taenia solium are often inadequate. This parasitic infection of the CNS, caused by the ingestion of T. solium eggs, is a leading cause of acquired epileptic seizures, making up a substantial percentage of cases, ranging from 26.3% to 53.8% in developing regions such as India and Latin America [1-8]. However, NCC is not confined to these endemic areas. The global movement of people due to immigration, travel, and other factors has facilitated the spread of NCC to more developed nations with well-organized healthcare systems. Individuals from endemic regions may either carry the infection themselves or act as transporters of T. solium, leading to the disease's emergence as a recognized health concern even in countries with advanced clinical setups. This underscores the importance of global health surveillance, proper diagnostic measures, and international cooperation to manage and prevent the spread of NCC beyond its traditional boundaries [1-8].

A research questionnaire is a structured data collection tool comprising a set of questions designed to gather specific information from respondents. It aims to understand their knowledge, opinions, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. The design of a questionnaire is often informed by the research objectives, hypotheses, and underlying theoretical framework. Questionnaires are frequently associated with a positivist philosophy, which emphasizes objective measurement and the quantification of variables, typical of the natural sciences. This alignment suggests that questionnaires are used to test hypotheses and establish patterns that can be generalized to larger populations. In research studies, questionnaires can serve as a primary data collection method, particularly in quantitative research [9-12]. They are also utilized in mixed-method studies, where they complement qualitative techniques such as interviews or focus groups, providing a more comprehensive view of the research problem. The development and use of questionnaires have indeed become a significant focus in research, especially in the healthcare area. This tendency reflects a growing recognition of the importance of patient-reported outcomes and patient perspectives on both clinical and non-clinical tendency of care. Questionnaires are invaluable tools for capturing subjective data, such as patients' perceptions of their health status, satisfaction with care, adherence to treatment, and quality of life. Absolutely the rigorous scientific standards are crucial for ensuring that research findings are credible, reproducible, and valuable. These standards help ensure that research contributes to the body of knowledge in a meaningful and reliable way [9-13].

In the present study, we are providing the systematic, well organized and comprehensive questionnaire based outcomes of patients with NCC of the North Indian population. These are no such extensive reports on the NCC patients. Questionnaires based outcomes of patients with NCC of the present study are contributed to evaluate the effectiveness of new interventions or combined therapeutic approaches, including Ayurveda, Yoga, and dietary modifications.

Material and Methods

Study design and research population

The present study was performed in qualitative and the quantitative manners, and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Institute of Medical Sciences (IMS), Banaras Hindu University (BHU), Varanasi (UP), India. The approval committee number is Dean/2023/EC/6806.

All the patients (N=50), who participated in the present study, were enrolled in the OPD of the department of neurology, IMS, BHU. Figure-1 represented the entire overview of the diagnosis of patients with NCC. All the diagnostically confirmed cases (MRI /CT scan based imaging) of NCC were included in the present study (Figure-2).

Questionnaire-based approach

Assessing patients with neurocysticercosis (NCC) using a questionnaire-based approach can be a valuable tool in both clinical practice and research settings. This method allows for a systematic evaluation of symptoms, quality of life, treatment response, and other patient-reported outcomes, which can help tailor individualized care and track disease progression. Here, we are presenting an overview of such assessments:

Personal Assessment

Age, sex, physical challenges, employment, marital status, education, dietary pattern and economical ground of all the NCC patients were assessed.

Symptom Assessment

-

- Seizure Frequency and Severity: Since seizures are the most common manifestation of NCC, questionnaires often include detailed queries about the type, frequency, duration, and impact of seizures on daily life.

- Headache and Neurological Symptoms: Assessing the presence, frequency, and severity of headaches, as well as other neurological symptoms, such as dizziness, and visual disturbances.

Data analysis

All the collected data of NCC patients were represented in the form of number/percentage/ mean value. The percentage/ mean value compared by Student‘t’ test for independent groups. The p value b 0.05 was considered significant. The data management and analysis were carried out using statistical software SPSS version 15.0.

Results

Personal outcomes

The NCC patients, who participated in the present study, were between 8 and 63 years of age with an average value of 22.80 ±12.21 years. Entire of these, 48% (24/50) of the patients were female and the 52% (26/50) were male. The significant difference was not observed (p>0.05). Physical challenges were observed in 4 % (2/50) case of NCC. On the ground of employment, 40% (20/50) of the patients were student, 18 % (9/50) were housewives, 10% (5/50) were employed and 32% (16/50) were unemployed. On the ground of marital status, 48% (24/50) patients were married and 52% (26/50) were unmarried. The significant difference was not observed (p>0.05). On the educational background, 90% (45/50) of the NCC patients were educated and 10% (5/50) were illiterate. The significant difference was observed (p<0.05). On the ground of dietary pattern, 84% (42/50) patients were taken the non-vegetarian diet and 16% (8/50) patients were consumed the vegetarian diet. The significant difference was observed (p<0.05). Economical ground showed the 88% (44/50) patients were middle class and 12% (6/50) patients were belonged to the lower middle class. The significant difference was observed (p<0.05).

Symptom outcomes

All the patients (N=50) with NCC showed the symptoms of seizure. The mean value of the duration of the disease was 3.78 +4.54 years. In all these, 84% (42/50) cases were represented the focal seizure and 16 % (18/50) represented the generalized seizure. The significant difference was observed (p<0.05). The mean value of the seizure frequency was 1.90 +1.57 for all the twenty two cases. Other symptoms, headache was represented by 80% cases (40/50), dizziness was represented by 96% cases (48/50) and vomiting after post-seizure was represented by 24% cases (12/50). Vision abnormality was found only 4% (2/50) cases and 96% (48/50) cases did not show it. The significant difference was observed (p<0.05). Family history of seizure was found positive for 20% (10/50) cases. The significant difference was observed (p<0.05). History of head trauma/ injury was found positive for 12% (6/50) cases.

Discussion

The present study aimed to develop a questionnaire to assess the clinical profiles of patients with NCC. The initial draft of the current questionnaire was developed based on a qualitative study. Here, fifty (N = 50) patients with NCC items were included. All these patients were belonged to the eastern UP and western Bihar (UP and Bihar are two states of India).

The age range from 8 to 63 years with an average age of 22.8 years, indicates a broad demographic in the study. This could reflect variability in how NCC affects different age groups and may provide insights into age-related differences in symptoms, treatment responses, or disease progression. The observation of a bimodal distribution of epilepsy incidence, including cases related to neurocysticercosis (NCC), is well-supported to our findings. Hauser et al. found that the incidence of epilepsy, including NCC, peaks during the first year of life and again after the age of 74. Similarly, Mani et al. and Banerjee et al. have identified a bimodal pattern, with peaks in early childhood and again in the 70s and 80s. On the basis of the outcome of one study, it was found that the range of the age of NCC patients was 23 to 50 years. This outcome also supported our findings [14-17].

Entire of these, 48% (24/50) of the patients were female and the 52% (26/50) were male. There is no significant difference observed between the numbers of male vs. female patients with NCC. This finding is also supported by the previous studies [14-17].

Based on the employment status of the 50 patients with neurocysticercosis (NCC), students are 40% (20 out of 50), housewives are18% (9 out of 50),employed people are10% (5 out of 50) and unemployed are 32% (16 out of 50).This data provides a snapshot of the demographic distribution of NCC patients concerning the employment status. It shows that a significant proportion is students, while the employed group is relatively smaller. There is not much information available about the employment status of the patients with NCC.

Outcomes of the present study, 48% of the patients with neurocysticercosis (NCC) were married, which accounts for 24 out of 50 patients. Meanwhile, 52% were unmarried, making up 26 out of the 50 patients. This suggests a fairly balanced distribution of marital status among the NCC patients, with a slight predominance of unmarried individuals. There is not much information available about the marital status of the patients with NCC.

The educational background of NCC patients, where 90% were educated and only 10% were illiterate, is indeed significant in several contexts. Educated individuals might have better access to information about hygiene, sanitation, and preventive measures against parasitic infections like Taenia solium, which causes neurocysticercosis. Awareness campaigns and educational materials can be more effectively communicated to those who are literate. Educated patients are generally more likely to understand their diagnosis and treatment plan, which can enhance medication adherence. They may better comprehend the importance of completing a course of anti-parasitic drugs, managing side effects, and following up with medical professionals. The higher proportion of educated patients could suggest that those with some level of education may seek medical help more promptly, recognize symptoms earlier, or have more access to healthcare facilities. This data could also reflect socioeconomic factors, as education often correlates with better living conditions and access to healthcare resources. It's important to consider how these factors might influence both the prevalence and management of NCC [18-20].

Significant majority of patients with neurocysticercosis (NCC) in this study were consuming a non-vegetarian diet. 84% of patients (42 out of 50) were on the non-vegetarian diet and 16% of patients (8 out of 50) on the vegetarian diet. This distribution could provide some insights into the dietary patterns associated with NCC cases in the studied population. In many regions, consuming undercooked or contaminated pork is a known risk factor for developing NCC, as the disease is caused by the larval stage of Taenia solium, the pork tapeworm [7, 21-24].

The socioeconomic background of neurocysticercosis (NCC) patients is quite insightful. With 88% of the patients belonging to the middle class and 12% to the lower middle class, this distribution suggests some interesting points. Middle-class individuals might have better access to healthcare services and awareness about conditions like NCC compared to those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. This could mean that middle-class patients are more likely to seek diagnosis and treatment. Being in the middle class may offer some financial stability, allowing patients to afford the necessary medication and treatment for NCC, which can involve costly imaging studies (like CT or MRI scans), anti-parasitic drugs, corticosteroids, and anticonvulsants. The finding also highlights the potential role of education and awareness in managing NCC. Middle-class families might have more access to health education and preventive measures (like proper sanitation and hygiene) that reduce the risk of NCC. However, despite this, the high prevalence of NCC in this group could indicate gaps in public health education or the persistence of risk factors such as poor food and water quality. There might be different health-seeking behaviors among socioeconomic groups. Middle-class individuals may be more proactive about getting treatment, whereas those from lower socioeconomic groups might delay seeking care due to financial constraints or lack of awareness. This socioeconomic pattern emphasizes the need for targeted public health strategies to improve awareness, prevention, and management of NCC across different economic backgrounds, especially for the lower middle class or those with limited access to healthcare [23, 25-27].

In the context of seizure pattern, the outcome of the present study indicates that among 50 cases of NCC, 42 cases (84%) presented with focal seizures, while the remaining 8 cases (16%) presented with generalized seizures. This distribution suggests that focal seizures are significantly more common in patients with NCC compared to generalized seizures. This could be reflective of the localization of cysts in the brain, which often affects specific areas leading to focal seizures [28-30].

The present study provides the clinical presentation and symptomatology in patients with neurocysticercosis (NCC).The mean seizure frequency among the 22 NCC cases was 1.90 with a standard deviation of ±1.57. This indicates that on average, patients experienced approximately 1 to 2 seizures, but the frequency varied widely among individuals. 80% of the cases (40 out of 50) experienced headaches, making it a common symptom among the NCC patients. 96% of the cases (48 out of 50) reported dizziness, suggesting it is one of the most prevalent symptoms in this group. 24% of the cases (12 out of 50) experienced vomiting after a seizure, indicating that while not as common as dizziness or headaches, post-seizure vomiting still affected a significant minority of patients. This study underscores the varied and often severe symptoms experienced by NCC patients, with a particularly high prevalence of dizziness and headaches [1-3, 31-32].

The present study reflects the prevalence of certain symptoms and risk factors among 50 cases of NCC. Vomiting post-seizure was observed in 24% of cases (12 out of 50), vision abnormalities were present in 4% of cases (2 out of 50) and absent in 96% of cases (48 out of 50).Family history of seizures was positive in 20% of cases (10 out of 50) and history of head trauma/injury was positive in 12% of cases (6 out of 50).These findings may help in understanding the prevalence of associated symptoms and risk factors in patients with NCC. Vision abnormalities were also reported in patients with NCC and also observed in the present study [33]. Report about the positive family history of seizure was only available in the cases of epilepsy [34], but this is not mentioned in NCC cases. The unique findings of our study were vomiting post-seizure, positive family history and history of head trauma/injury.

This study performed the assessment of the clinical profile of patients with NCC in the North Indian population and evaluated the effectiveness of new interventions or combined therapeutic approaches. By using questionnaires, the study gathers outcomes to understand how integrated approaches, such as Ayurveda, Yoga, and dietary modifications affect the health and well-being of NCC patients. The significance of this study lies in its focus on the potential benefits of these holistic methods, particularly in managing symptoms, reducing side effects, and improving quality of life. The findings could provide valuable insights into alternative or complementary strategies for managing NCC beyond conventional allopathic treatments, potentially leading to more personalized and comprehensive care plans.

Funding

This study did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Consent for publication

The patient provided written informed consent for the publication of this report and the accompanying images.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgments

The authors pay sincere thanks to patients, who were involved and gave her consent for the utilization of the clinical reports and images.

References

1. Garcia, Hector H et al. “Clinical symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of neurocysticercosis.” The Lancet. Neurology vol. 13,12 (2014): 1202-15. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70094-8

2. Del Brutto, Oscar H. “Neurocysticercosis.” The Neurohospitalist vol. 4,4 (2014): 205-12. doi:10.1177/1941874414533351

3. Michelet, L., Fleury, A., Sciutto, E., et al. Human neurocysticercosis: comparison of different diagnostic tests using cerebrospinal fluid [published correction appears in J Clin Microbiol. 2012 ;50(1):212]. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(1):195-200. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01554-10

4. Singh, Gagandeep et al. “From seizures to epilepsy and its substrates: neurocysticercosis.” Epilepsia vol. 54,5 (2013): 783-92. doi:10.1111/epi.12159

5. Garcia, Hector H et al. “Taenia solium Cysticercosis and Its Impact in Neurological Disease.” Clinical microbiology reviews vol. 33,3 e00085-19. 27 May. 2020, doi:10.1128/CMR.00085-19

6. Coyle, Christina M, and Herbert B Tanowitz. “Diagnosis and treatment of neurocysticercosis.” Interdisciplinary perspectives on infectious diseases vol. 2009 (2009): 180742. doi:10.1155/2009/180742

7. Prasad, Kashi Nath et al. “Human cysticercosis and Indian scenario: a review.” Journal of biosciences vol. 33,4 (2008): 571-82. doi:10.1007/s12038-008-0075-y

8. Del Brutto, Oscar H. “Neurocysticercosis: a review.” TheScientificWorldJournal vol. 2012 (2012): 159821. doi:10.1100/2012/159821

9. Aaronson, N K et al. “The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute vol. 85,5 (1993): 365-76. doi:10.1093/jnci/85.5.365

10. Boynton, Petra M, and Trisha Greenhalgh. “Selecting, designing, and developing your questionnaire.” BMJ (Clinical research ed.) vol. 328,7451 (2004): 1312-5. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7451.1312

11. Boynton, Petra M. “Administering, analysing, and reporting your questionnaire.” BMJ (Clinical research ed.) vol. 328,7452 (2004): 1372-5. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7452.1372

12. Ranganathan, Priya, and Carlo Caduff. “Designing and validating a research questionnaire - Part 1.” Perspectives in clinical research vol. 14,3 (2023): 152-155. doi:10.4103/picr.picr_140_23

13. Kishore, Kamal et al. “Practical Guidelines to Develop and Evaluate a Questionnaire.” Indian dermatology online journal vol. 12,2 266-275. 2 Mar. 2021, doi:10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_674_20

14. Mani, K S et al. “The Yelandur study: a community-based approach to epilepsy in rural South India--epidemiological aspects.” Seizure vol. 7,4 (1998): 281-8. doi:10.1016/s1059-1311(98)80019-8

15. Del Brutto, Oscar H, and Victor J Del Brutto. “Calcified neurocysticercosis among patients with primary headache.” Cephalalgia : an international journal of headache vol. 32,3 (2012): 250-4. doi:10.1177/0333102411433043

16. Banerjee, Tapas Kumar et al. “A longitudinal study of epilepsy in Kolkata, India.” Epilepsia vol. 51,12 (2010): 2384-91. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02740.x

17. Nijman, H L I et al. “Fifteen years of research with the Staff Observation Aggression Scale: a review.” Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica vol. 111,1 (2005): 12-21. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00417.x

18. Nateros, Fernando et al. “Older Age in Subarachnoid Neurocysticercosis Reflects a Long Prepatent Period.” The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene vol. 108,6 1188-1191. 1 May. 2023, doi:10.4269/ajtmh.22-0791

19. Ghosh R, Arunjyoti B. Educational Needs of Persons with Epilepsy: A Qualitative Study. Indian Journal of Continuing Nursing Education 24 (2023):p 74-79. DOI: 10.4103/ijcn.ijcn_118_21

20. Sureka RK, Sureka R. Knowledge, attitude, and practices with regard to epilepsy in rural North-West India Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 10 (2007):160–164.

21. Cochrane, J. “Patient education: lessons from epilepsy.” Patient education and counselling vol. 26,1-3 (1995): 25-31. doi:10.1016/0738-3991(95)00726-g

22. Khanal N, Shrestha R .Seizure commonly associated with Neurocysticercosis are not linked with pork meat diet. A retrospective analysis. Asian Journal of Medical Sciences. 10(2019) : Issue 5.

23. Ahmad, Rumana et al. “Neurocysticercosis: a review on status in India, management, and current therapeutic interventions.” Parasitology research vol. 116,1 (2017): 21-33. doi:10.1007/s00436-016-5278-9

24. Prasad, Kashi Nath. “My experience on taeniasis and neurocysticercosis.” Tropical parasitology vol. 11,2 (2021): 71-77. doi:10.4103/tp.tp_6_21

25. Khurana, Sumeeta et al. “Prevalence of anti-cysticercus antibodies in slum, rural and urban populations in and around Union territory, Chandigarh.” Indian journal of pathology & microbiology vol. 49,1 (2006): 51-3.

26. Singh, B B et al. “Estimation of the health and economic burden of neurocysticercosis in India.” Acta tropica vol. 165 (2017): 161-169. doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.01.017

27. Rajkotia, Yogesh et al. “Economic burden of neurocysticercosis: results from Peru.” Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene vol. 101,8 (2007): 840-6. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.03.008.

28. Duque, Kevin R, and Jorge G Burneo. “Clinical presentation of neurocysticercosis-related epilepsy.” Epilepsy & behavior : E&B vol. 76 (2017): 151-157. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2017.08.008

29. Medina, Marco T et al. “Prevalence, incidence, and etiology of epilepsies in rural Honduras: the Salamá Study.” Epilepsia vol. 46,1 (2005): 124-31. doi:10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.11704.x

30. Medina, Marco T et al. “Reduction in rate of epilepsy from neurocysticercosis by community interventions: the Salamá, Honduras study.” Epilepsia vol. 52,6 (2011): 1177-85. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02945.x

31. Murthy, Jagarlapudi M K, and Vijay Seshadri. “Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and seizure outcomes of epilepsy due to calcific clinical stage of neurocysticercosis: Study in a rural community in south India.” Epilepsy & behavior : E&B vol. 98,Pt A (2019): 168-172. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.07.024

32. Thamilselvan, Piriyatharisini et al. “A Stratified Analysis of Clinical Manifestations and Different Diagnostic Methods of Neurocysticercosis-Suspected Tamilian Population Residing in and Around Puducherry.” Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR vol. 11,5 (2017): DC10-DC15. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2017/23711.9844

33. Snyder, M Harrison et al. “Neurocysticercosis Presenting as an Isolated Suprasellar Lesion.” World neurosurgery vol. 141 (2020): 352-356. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2020.05.212

34. Ghiasian, Masoud et al. “Investigating the relationship of positive family history pattern and the incidence and prognosis of idiopathic epilepsy in epilepsy patients.” Caspian journal of internal medicine vol. 11,2 (2020): 219-222. doi:10.22088/cjim.11.2.219.

Figure:

Figure 1: Representation of the overview of the diagnosis of patients with NCC.

Figure 2: Representation of the diagnostic confirmation of (a) MRI of nodular cysticerci (multiple)

, (b) CT scan of calcified cysticerci (multiple)