Case Report

Clinical Acumen: A 58-Year-Old Male Presenting with Rapidly progressive Dementia

Sanchit Shailendra Chouksey1, Anand Vardhan2, Pranjali Batra3, Varun Kumar Singh4, Rameshwar Nath Chaurasia1*

Address for Correspondence: Rameshwar Nath Chaurasia, M.D., D.M., Professor and Head, Department of Neurology Institute of Medical Science, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi-221005,

Email: goforrameshwar@gmail.com

Introduction

Neurocysticercosis (NCC) is the central nervous system infection by the larval stage of the pork tapeworm Taenia solium, which is endemic in most developing countries and remains one of the world's leading causes of seizures (1). NCC presents clinically similarly to a wide range of neurological conditions, making clinical diagnosis challenging, particularly in low-income countries. NCC presentation can range from asymptomatic to sudden death, depending on the patient's immune response and the number, size, stage, and location of the cysts (1). Rapidly progressive dementia can be a presenting manifestation of NCC. Here, we present a case of 60-year-old male presented with rapidly progressive dementia later found to have neurocysticercosis on imaging.

Case report

A man in his late 60s presented with one and half months of progressive cognitive decline. Two months before, he developed a fever that was low-grade, intermittent, and non-recorded, for which he was taking over-the-counter medication from the local medical shop. Fever lasted for 10 days without any diurnal variation. One and half months earlier, he started having difficulty holding longer coherent conversations about even basic events. He could not continue managing the family finances and was neglecting his hygiene. He became uncooperative and disoriented over the next few days. His symptoms further worsened so that he required assistance with mobility, would get lost in his house, and was not able to recognize his family. In the last 10 days, he started having visual hallucinations and became apathetic. He had no loss of consciousness, seizure, myoclonus, or headache. He has been a known case of type 2 diabetes mellitus for the past 5 years, which was well controlled on medication. He was a vegetarian, tobacco chewer, and social drinker.

On examination, he was conscious, not oriented to time and person, but was oriented to place. His forward and backward attention is 5 and 3, respectively. He was confabulating and unable to identify family members. His speech was clear and fluent, with intact repetition and decreased verbal output. He had a mini-mental state examination score of 14/30 with impairment in orientation, calculation, recall, and copying. He had a frontal assessment battery score of 3/18 with only persevered environmental autonomy. The remaining cranial nerve, motor, sensory, coordination, and gait examinations were unremarkable, with no signs of meningeal irritation. His deep tendon reflexes were normal, and plantar reflexes were flexor bilaterally. There were frontal release signs, including palmomental, grasp, and glabellar tap, without any startle reflex or myoclonus.

Questions

What is the expected localization of his presentation?

What possible diagnoses should be considered?

Inattention, working memory, dysexecutive features, apathy, and frontal release signs suggested frontal lobe involvement. Impaired recent memory and well-formed hallucinations point towards the involvement of the temporal lobe. Visuospatial disorientation localizes to the non-dominant parietal lobe. His significant cognitive decline indicated widespread cortical dysfunction.

Differential diagnosis, including vascular (e.g., Ischemic or hemorrhagic infarction - single strategic lesion or multifocal, cerebral venous thrombosis, cerebral amyloid angiopathy), infective (e.g., bacterial/viral/fungal encephalitis, neurocysticercosis), toxic-metabolic (e.g., vitamin B12 and B1 deficiencies, endocrine and electrolyte abnormalities), autoimmune, malignancy/metastasis-related (e.g., carcinomatous meningitis), iatrogenic (e.g., illicit drug use), neurodegenerative (e.g., prion disease, dementia with Lewy bodies) and systemic disease. (2)

The vascular lesion usually has sudden onset involvement with focal neurological symptoms/signs, which is not the case in our patient. Autoimmune, malignancy, iatrogenic, and systemic diseases were ruled out as there was no apparent history to suggest these possible causes. Neurogenerative Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) tends to have early neurological signs with startle response or myoclonus and visual field deficit, which was not seen in this case. We have also taken into account infectious causes, which are frequently accompanied by systemic symptoms like fever and meningism. This patient had diabetes and a fever, so the possibility of an infectious cause cannot be ruled out. When considering the causes of toxicity or metabolic issues, it's important to take into account factors such as vitamin B12 deficiency, which may be influenced by a vegetarian diet and a history of alcohol intake.

Questions

What investigations are you likely to order?

The following tests are conducted: complete blood count with differential, basic metabolic panel including calcium, magnesium, and phosphate levels, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) test, rapid plasma regain test, liver and thyroid function tests, rheumatological screen with erythrocyte sedimentation rate, antinuclear antibodies, and C reactive protein, urinalysis for urine, toxicology, and culture, cerebrospinal fluid analysis for cell count with differential, protein, glucose, IgG index, oligoclonal bands, venereal disease laboratory test (VDRL), 14-3-3 protein research, tau, cryptococcal antigen, viral PCRs, Gram stain and bacterial culture, fungal culture, acid-fast bacilli stains and cultures, cytology, and flow cytometry with imaging, including Magnetic resonance scan of the brain with and without contrast, and chest radiograph.

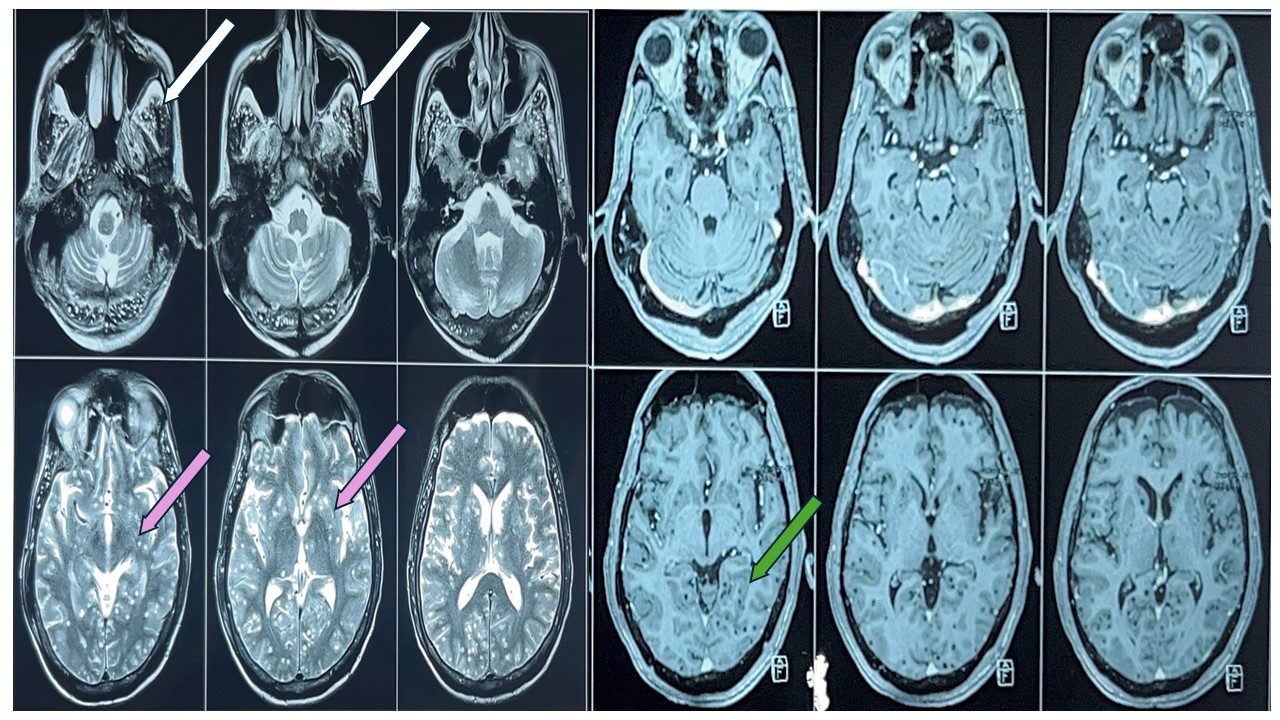

Given the asset restrictions in our setting, the patient went through a designated and stepwise workup. His complete blood count, renal, liver, and electrolytes were unremarkable. Serology for hepatitis B, C, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) were negative. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 35 mm/hr, and the C-reactive protein level was 1.2 mg/dL.His Vitamin B12, folate, and serum homocysteine levels were normal. Computed tomography scan of head was within normal limit. The electroencephalogram (EEG) revealed a slowed background rhythm without epileptiform discharges, which is indicative of moderate encephalopathy.Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) showed a normal pressure of 10 cm of water with normal cells, protein, sugar, and no bacterial or fungal growth. CSF cartridge-based nucleic acid amplification test (CBNAAT), VDRL and viral panel reports came negative. Noncontract computed tomography (CT) head was within normal limit. Magnetic resonance imaging of the Brain (MRI) with contrast was done, which showed a starry sky appearance, suggesting multiple NCCs (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Multiple T2 hyperintense lesions seen in bilateral cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres as depicted by white arrow (temporal lobe) and pink arrow (gangliocapsular region). There is no contrast enhancement of these lesions in the post-Gd images as depicted by green arrow (medial temporal lobe) likely multiple calcified granuloma suggestive of neurocysticercosis.

Based on imaging, diagnosis of neurocysticercosis was kept. He was managed with steroids, anti-seizure medication and other supportive treatment. He was discharged after improvement, and regular follow-up was advised.

Discussion

The term "rapidly progressive dementia" (RPD) is described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), Fourth Edition (3) as a condition marked by a rapid deterioration in cognitive function, resulting in the onset of dementia within a relatively short timeframe, typically less than one or two years.(2). This broad description encompasses a wide range of diverse illnesses, including prion diseases, immune-mediated, viral, and metabolic encephalopathies, as well as abnormally rapid presentations of other neurodegenerative diseases. Studies have shown that 20–30% of patients do not respond to medical treatment, and many have an unidentified cause (4). While science development provides us with instruments to address RPD, it is crucial to emphasize specific elements. Anuja P et al. showed that 31.9 % of cases of RPD had infectious etiology, out of which 7.6% had NCC (5). The most compromised cognitive domains were verbal memory, language, visuospatial skills, and executive processes. (6,7). Cognitive impairment can result from many causes operating alone or in conjunction with mechanisms related to local inflammatory (parasitic) reactions, vascular lesions, immune-mediated reactions, or secondary epilepsy caused by NCC, as well as antiepileptic medicines (8).

Neuroimaging visualization of cysts or larvae in brain tissue is the only way to make a definitive clinical diagnosis (9); in some instances, intracranial cystic calcification is the only evidence of the disease. Acute symptomatic lesions are best visualized on contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance (MR) imaging. However, chronic lesions are best visualized on noncontract CT as hyperdense calcifications because MR imaging signal voids associated with chronic calcified lesions are difficult to identify on all sequences. The initial stage of larval invasion (noncystic) is typically not visible on imaging due to the frequent absence of edema at this point. However, in some cases, lesions may produce edema and focal enhancement before progressing to a cystic form (10).

Neuroimaging, serological testing, and a thorough clinical examination are all well-established ways to diagnose NCC. Every strategy has its advantages and downsides, some finding success at diagnosing NCC contamination at various stages (sores, calcified pimples). Chemotherapy, surgical removal of the cysts, and/or symptomatic treatment (with or without cyst removal) are all options for treating the condition. Ordinarily, treatment includes the organization of a mix of cysticidal endlessly medications to reduce side effects (11).

Conclusion

- Rapidly progressive dementia (RPD) can be one of the manifestations of NCC.

- A high level of suspicion and keen scrutiny are required to identify the NCC, especially in RPD, as evidence of exposure may be unavailable.

- Although cognitive impairment and neuropsychiatric disorders are frequent signs of NCC, they remain poorly understood.

- Contrast-enhanced MR imaging is best imaging technique for various stages of NCC and different sites.

References

- Singh G, Burneo JG, Sander JW. From seizures to epilepsy and its substrates: neurocysticercosis. Epilepsia 2013; 54: 783–92.

- Geschwind MD. Rapidly progressive dementia. Continuum 2016;22:510–37.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edn (American Psychiatric Association, 1994).

- Datri L, Quiroga J, Reisin R, Rojas G, Young P. Análisis de 6 casos Rapidly progressive dementia. 2018. Mar, Deterioro cognitivo rápidamente evolutivo.

- Anuja P, et al. Rapidly progressive dementia: an eight year (2008–2016) retrospective study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0189832. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189832.

- Ciampi de Andrade D, Rodrigues CL, Abraham R, et al. Cognitive impairment and dementia in neurocysticercosis: a cross-sectional controlled study. Neurology. 2010;74:1288–1295.

- Rodrigues CL, Andrade DC, Livramento JA, et al. Spectrum of cognitive impairment in neurocysticercosis: differences according to disease phase. Neurology. 2012;78:861–866.

- Agapejev S. Clinical and epidemiological aspects of neurocysticercosis in Brazil: a critical approach. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2003;61:822–828.

- Del Brutto OH. Twenty-five years of evolution of standard diagnostic criteria for neurocysticercosis. How have they impacted diagnosis and patient outcomes? Expert Rev Neurother. (2020) 20:147–55. doi: 10.1080/14737175.2020.1707667.

- Lè Ne Carabin H, Ndimubanzi PC, Budke CM, Nguyen H, Qian Y, Cowan LD, et al. Clinical manifestations associated with neurocysticercosis: a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. (2011) 5:e1152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001152.

- Wang W, Garcia HH, Gonzales I, Bustos JA, Saavedra H, Gavidia M, et al. Combined antiparasitic treatment for neurocysticercosis. Lancet Infect Dis. (2015) 15:265. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)70047-2.