Review

Headache and its Management: A brief Review

Headache and its Management: A brief Review

Vineeta Singh, Deepika Joshi, Anand Kumar

Anand Kumar , Associate Professor, Department of Neurology, IMS, BHU, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India.

Email: anand.2005.02@gmail.com

Abstract:

Headaches are one of the most common neurological disorders, affecting nearly 95% of the global population at some point in their lives. With a one-year incidence rate close to 50% in adults, headaches are a significant public health concern. They account for approximately 10% of general practitioner consultations and a substantial proportion of neurology consultations and hospital admissions. The World Health Organization ranks headaches among the top ten causes of disability, particularly among women, where the impact is comparable to that of chronic diseases like arthritis and diabetes. Despite advances in understanding and treatment, headaches remain the third leading cause of disability globally, contributing to significant direct and indirect healthcare costs. These costs include medical expenses, lost productivity, and diminished quality of life. The global prevalence of tension headaches and migraines underscores the substantial burden of these conditions. Moreover, the higher prevalence of headaches in lower socioeconomic groups suggests that socioeconomic factors play a crucial role in the incidence and management of headaches. This review aims to explore the historical context, epidemiology, and comprehensive strategies to manage this pervasive condition.

Keywords: Headache, Neurological disorders, Epidemiology, Migraine, Tension headache, Chronic pain

Introduction

A headache is a pain in or around the head. It can be a dull ache, a sharp throbbing pain, or a pressure-like feeling. Headaches can range in severity from mild to severe and can last for a few minutes to several days. About 95% of the general population has experienced a headache at some point in their lives, with a one-year incidence of nearly one in two adults. Headache accounts for 1 in 10 general practitioner (GP) consultations, 1 in 3 neurology consultations and 1 in 5 acute hospital admissions [1]. The World Health Organization ranks headaches among the top 10 causes of disability, and in women, headaches are in the top five, with an impact similar to that of arthritis, diabetes, and more severe asthma [2].

The Ebers Papyrus (1200-1500 BC) mentions headaches and other nervous disorders. Visual symptoms associated with headaches were described by Hippocrates in 400 BC [3]. Aretaeus proposed one of the first classifications of headaches around 200 AD. Regarding the treatment of headaches, there is evidence of Neolithic skull drilling as far back as 9,000 years ago, suggesting some of the earliest therapeutic methods. Hippocrates described cupping, which uses cups to create a partial vacuum to induce blood flow to the site of pain in cases of severe headaches, but warned against treating severe causes of headaches. More benign. Aretaeus recommends using cupping if drawing blood from the arm or forehead does not relieve headache symptoms.

In addition, headache syndrome causes about 12 million medical visits each year in the United States, costing more than $78 billion per year in direct and indirect costs. Direct costs include outpatient services, medications, office or clinic visits, emergency department visits, laboratory and diagnostic services, and treatment management of side effects [4]. Indirect costs include impact on a patient's education level, career, income, social acceptance, psychological and emotional control of headaches/life, loss of productive workday, household chores and social activities. The lifetime incidence of any type of headache is 96%. The global prevalence of tension headaches is 40% and migraine is 10%. Of the 301 acute and chronic diseases identified by the Global Burden of Disease study, the two types of headaches that ranked as having the highest incidence were tension headaches and migraines [5].

Headaches are currently the third leading cause of disability worldwide, measured in years of life lost due to disability. The age-adjusted prevalence of headache (16.1%) in US adults was third after low back pain (28.1%) and knee pain (19.5%) in a study of chronic pain by the Institute of Medicine. In the United States, headache prevalence is approximately 75% higher in the lowest socioeconomic groups than in the highest socioeconomic groups. The higher prevalence also applies to other causes of chronic pain, including low back pain, knee pain, and neck pain. In short, the burden of chronic pain is greater due to headache (and other chronic pain syndromes) appear to be the cause. people with more limited resources to deal with chronic pain.

- Epidemiology

Headache disorders are among the most common neurological disorders in the world. According to the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2021 study, the estimated global prevalence of any headache disorder in adults was 52.0% in 2021. This means that more than half of all adults in the world will experience a headache at least once in a year. The prevalence of headache disorders varies by type. According to the GBD 2021 study, the estimated global prevalence of migraine in adults was 14.7% in 2021, while the estimated global prevalence of tension-type headache in adults was 34.9% in 2021. Headache disorders are also more common in women than in men. According to the GBD 2021 study, the estimated global age-standardized prevalence of any headache disorder in adult women was 57.8% in 2021, while the estimated global age-standardized prevalence of any headache disorder in adult men was 44.4% in 2021. The prevalence of headache disorders also varies by age group. According to the GBD 2021 study, the estimated global age-standardized prevalence of any headache disorder was highest in the 18-30 age group (63.9%) and lowest in the 65-74 age group (45.1%) [6].

-

- In India

Headache disorders are very common in India. A study published in 2021 found that the one-year prevalence of any headache in India was 63.9%, with a female preponderance of 4:3. The age-standardized 1-year prevalence of migraine was 25.2%, which is higher than the global average of 14.7% [7]. Further, the prevalence of tension-type headache in India was 35.1%. This is also higher than the global average of 34.9%. A study published in 2021 found that the one-year prevalence of any headache was 73.0% in women and 54.4% in men. The age-standardized 1-year prevalence of migraine was 32.4% in women and 18.6% in men. The prevalence of headache disorders in India also increases with age. A study published in 2019 found that the prevalence of tension-type headache was highest in the 41-50 age group (37.2%). The prevalence of migraine was highest in the 18-30 age group (28.4%) [8].

- Classification

The International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) was first published in 1988 and has now gone through 2 revisions, most recently in 2013. The classification, freely available online at: https://www.ichd-3.org/, contains explicit criteria based on phenomenology for the diagnosis of many types of headaches. The International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3 beta criteria) is a comprehensive classification system for all known headache disorders. It is published by the International Headache Society (IHS) and is used by clinicians and researchers around the world [9].

The ICHD-3 criteria divide headache disorders into four main categories:

The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-3), is a comprehensive system used globally by healthcare professionals to diagnose and classify headache disorders. It was developed by the International Headache Society (IHS) and is recognized as the standard for classifying headache disorders.

Structure of ICHD-3

The ICHD-3 is divided into four main parts, each covering a specific category of headache disorders:

Part 1: Primary Headache Disorders

These are headaches not caused by another medical condition. They are the most common types of headaches.

- Migraine

- Migraine without aura

- Migraine with aura

- Chronic migraine

- Complications of migraine

- Probable migraine

- Tension-Type Headache (TTH)

- Infrequent episodic TTH

- Frequent episodic TTH

- Chronic TTH

- Probable tension-type headache

- Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalalgias (TACs)

- Cluster headache

- Paroxysmal hemicrania

- Short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with conjunctival injection and tearing (SUNCT)

- Short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with cranial autonomic symptoms (SUNA)

- Hemicrania continua

- Other Primary Headache Disorders

- Primary stabbing headache

- Primary cough headache

- Primary exercise headache

- Primary headache associated with sexual activity

- Hypnic headache

- New daily persistent headache (NDPH)

Part 2: Secondary Headache Disorders

These headaches result from other medical conditions, such as trauma, vascular disorders, or infections.

- Headache Attributed to Trauma or Injury

- Headaches related to head or neck trauma.

- Headache Attributed to Vascular Disorders

- Headaches caused by conditions like stroke, transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), arteriovenous malformations, etc.

- Headache Attributed to Non-Vascular Intracranial Disorders

- Including conditions like increased intracranial pressure, brain tumors, etc.

- Headache Attributed to a Substance or Its Withdrawal

- Headaches caused by the use or withdrawal of substances, including medication-overuse headache.

- Headache Attributed to Infection

- Headaches resulting from systemic or intracranial infections.

- Headache Attributed to Disorders of Homeostasis

- Caused by factors like fasting, high blood pressure, or thyroid disorders.

- Headache or Facial Pain Attributed to Disorders of the Cranium, Neck, Eyes, Ears, Nose, Sinuses, Teeth, Mouth, or Other Facial or Cervical Structures

- For example, sinus headache.

- Headache Attributed to Psychiatric Disorder

- Although less common, headaches can be linked to psychiatric conditions.

Part 3: Painful Cranial Neuropathies, Other Facial Pains, and Other Headaches

This category includes conditions where the pain originates from the nerves in the head or face.

- Painful Cranial Neuropathies and Other Facial Pains

- Trigeminal neuralgia

- Glossopharyngeal neuralgia

- Occipital neuralgia

- Other Primary and Secondary Headaches

- Headaches not covered in the above categories.

Part 4: Appendix

The appendix contains research criteria for new and rare headache disorders that are not yet fully validated but are of interest for further study [9].

A headache examination is a physical examination that is performed to assess the cause of a headache.

The doctor may also ask you about your headache history, including the following:

- When did the headaches start?

- How often do you have headaches?

- How long do your headaches last?

- Where is the pain located?

- What does the pain feel like?

- What makes the headaches better or worse?

- Do you have any other symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, dizziness, or light sensitivity?

- Do you have visual symptoms, hearing difficulties, neck pain, back pain, bladder or bowel symptoms, cognition or other symptoms before, during or after headache

The doctor will use the information from the examination and your headache history to make a diagnosis and develop a treatment plan.

The examination may include the following:

- Vital signs: The doctor will check your blood pressure, heart rate, and temperature [10].

- Local examination: The doctor will also try to look for nay local tenderness at skull, neck, face, sinuses.

- Ophthalmological examination: Detail ophthalmological examination along with fundus examination is very important for every headache patient specially the doubt of secondary headache is there.

- Neurological examination: The doctor will check your reflexes, power, sensory system, coordination, and balance as per your history.

If the doctor suspects that your headache may be caused by an underlying medical condition, they may order additional tests, such as blood tests, imaging studies, or a lumbar puncture [11].

Here are some tips for preparing for a headache examination:

- Make a list of all the medications, supplements, and herbs you are taking.

- Bring a headache diary, if you keep one.

- Think about what triggers your headaches and what makes them better or worse.

- Write down any questions you have for the doctor.

A neurological examination of headache is a focused examination of the nervous system to assess for any abnormalities that could be causing the headache. The examination typically includes the following:

- Mental status examination: This assesses the patient's level of consciousness, orientation, memory, and cognitive function [12].

- Cranial nerve examination: This assesses the function of the 12 cranial nerves, which control various sensory and motor functions in the head and neck [13].

- Motor examination: This assesses the patient's muscle strength, coordination, and reflexes [14].

- Sensory examination: This assesses the patient's sensation to touch, pain, temperature, and vibration [14].

The doctor may also perform additional tests, such as the following:

- Funduscopic examination: This examines the retina at the back of the eye for any signs of papilledema, which can be caused by increased intracranial pressure [15].

- Meningismus examination: This assesses for signs of meningeal inflammation, such as neck stiffness, Kernig's sign, and Brudzinski's sign [16].

The findings of the neurological examination can help the doctor to narrow down the possible causes of the headache and to determine whether additional tests are needed.

Here are some specific findings on neurological examination that can be associated with different types of headache:

- Migraine: Migraine headaches may be associated with neurological findings such as photophobia (sensitivity to light), phonophobia (sensitivity to sound), and aura (a visual or sensory disturbance that precedes the headache).

- Tension-type headache: Tension-type headaches are not typically associated with neurological findings, but they may be associated with tenderness of the scalp and neck muscles.

- Cluster headache: Cluster headaches may be associated with neurological findings such as ipsilateral ptosis (drooping eyelid) and miosis (pupillary constriction).

- Secondary headache disorders: Secondary headache disorders can be associated with a variety of neurological findings, depending on the underlying cause. For example, headaches caused by a brain tumor may be associated with focal neurological deficits such as weakness, numbness, or seizures.

It is important to note that the absence of neurological findings on examination does not rule out the possibility of a serious underlying cause of headache. If you have any concerns about your headache, please see a doctor for evaluation.

-

- Neurological scale:

There are a number of neurological scales that can be used to assess the severity of headache and to monitor the response to treatment. Some of the most commonly used neurological scales for headache examination include:

- Headache Impact Test (HIT-6): The HIT-6 is a 6-item questionnaire that assesses the impact of headache on daily activities. It is a simple and easy-to-use scale that can be used to monitor the effectiveness of treatment over time [17].

- Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS): The MIDAS is a 7-item questionnaire that assesses the impact of migraine on daily activities and work productivity. It is a more detailed scale than the HIT-6 and can be used to track progress over time and to identify patients who are at high risk for disability [18].

- Migraine Headache Index (MHI): The MHI is a 5-item scale that assesses the severity and frequency of migraine headaches. It also includes items to assess the impact of migraine on daily activities and work productivity [19].

- Migraine Visual Analog Scale (MVAS): The MVAS is a 100 mm visual analog scale that assesses the severity of migraine pain. It is a simple and easy-to-use scale that can be used to assess the response to pain medications [20].

- Migraine-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (MSQ): The MSQ is a 15-item questionnaire that assesses the impact of migraine on quality of life. It includes items to assess the impact of migraine on physical functioning, emotional functioning, social functioning, and role limitations [21].

The choice of which neurological scale to use will depend on the specific needs of the patient and the purpose of the assessment. For example, the HIT-6 and MIDAS are commonly used in clinical practice to assess the impact of headache on daily activities and work productivity. The MHI, MVAS, and MSQ are commonly used in research studies to assess the effectiveness of migraine treatments.

5. Patient History and Examination

When taking a headache history, the doctor will ask questions about the following [22]:

- Onset: When did the headaches start?

- Frequency: How often do you have headaches?

- Duration: How long do your headaches last?

- Location: Where is the pain located?

- Quality: What does the pain feel like? (e.g., throbbing, dull, aching)

- Associated symptoms: Do you have any other symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, dizziness, or light sensitivity?

- Triggers: What makes your headaches better or worse?

- Medical history: Do you have any other medical conditions? Are you taking any medications?

- Family history: Do any other family members have headaches?

Headache Examination

Indications for neuroimaging in headache patients

Neuroimaging is not typically recommended for all headache patients. However, there are a number of situations in which neuroimaging may be indicated, such as:

- New onset of headache after the age of 50

- Sudden onset of severe headache

- Headache accompanied by fever, neck stiffness, or confusion

- Headache that is associated with a neurological deficit, such as weakness, numbness, or seizures

- Headache that is worse when lying down or straining

- Headache that is accompanied by vision changes, such as double vision or blurred vision

- Headache that is resistant to treatment

- Headache with a family history of neurological disorders

Neuroimaging findings in headache patients

The most common neuroimaging findings in headache patients are nonspecific abnormalities, such as white matter hyperintensities and incidental findings. However, neuroimaging can also identify serious underlying causes of headache, such as brain tumors, stroke, and vascular malformations [23].

Interpretation of neuroimaging findings

It is important to note that neuroimaging findings should be interpreted in the context of the patient's clinical presentation. For example, a nonspecific abnormality on neuroimaging does not necessarily mean that the patient has a serious underlying cause of headache. Conversely, a serious underlying cause of headache may be present even if the neuroimaging is normal.

6. Diagnosis

The doctor will use the information from the headache history and examination to make a diagnosis and develop a treatment plan. Treatment will depend on the underlying cause of the headache. For some types of headaches, such as tension-type headaches, prophylactics may be sufficient. For other types of headaches, such as migraine headaches, prescription medications may be necessary. In some cases, lifestyle changes, such as stress management and regular exercise, can also help to reduce the frequency and severity of headaches.

A detailed history of the patient’s headache is of paramount importance in making the correct diagnosis. Information gathered in the history is compared to the diagnostic criteria to create the best diagnostic match. The history records details about the headache such as frequency, duration, character, severity, location, quality and triggering, aggravating and alleviating features. Age of onset is extremely important and a family history of headache should be explored. Lifestyle features including diet, caffeine use, sleep habits, work and personal stress are important to obtain. Finally, details of any comorbid conditions, such as an associated sleep disorder, depression, anxiety and an underlying medical disorder are also useful.

The examination in headache is based upon the general neurological examination. Additional features include examination of the superficial scalp vessels, neck vessels, dentition and bite, the temporomandibular joints, and cervical and shoulder musculature. Pericranial muscle tenderness is thought to be an important physical finding in the diagnosis of tension-type headache [24, 25].

The Diagnostic Evaluation - Indications for Imaging

There is no diagnostic test for migraine and evidence suggests that, in the specific setting of migraine with a normal neurological examination, imaging is overwhelmingly likely to be unremarkable. There remain appropriate indications for imaging in the evaluation of headache and should be considered when various “red flags” are present.

In practice, many patients with lifelong headache disorders will end up undergoing imaging at least once and approximately 1 billion dollars are spent every year on unnecessary brain imaging studies [25].

7. Types of Headaches

Headaches are broadly divided into primary and secondary.

Primary Headache:

Most common types of primary headache are:

- Tension-type headache (TTH): TTH is the most common type of headache, affecting about 70% of the population. It is characterized by a dull, aching sensation in the head, often described as a "tight band" around the forehead or temples. TTH can be triggered by stress, anxiety, depression, poor posture, and lack of sleep [26].

- Migraine headache: Migraine is a severe headache that is often accompanied by other symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, sensitivity to light and sound, and visual disturbances. Migraine headaches are caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors. Common triggers for migraine headaches include stress, changes in hormones, certain foods and drinks, and weather changes [27].

- Cluster headache: Cluster headaches are rare but very painful headaches. They occur in clusters, which means that people will have several headaches in a row over a period of days or weeks. Cluster headaches are more common in men than in women and are often triggered by smoking and alcohol consumption [28].

Other types of primary headache include:

- New daily persistent headache (NDPH): NDPH is a chronic headache that occurs daily for at least 3 months. It is not clear what causes NDPH, but it may be triggered by a head injury, infection, or medication overuse [29].

- Hemicrania continua: Hemicrania continua is a chronic headache that occurs on one side of the head for at least 3 months. It is characterized by a moderate, constant pain that is often accompanied by other symptoms, such as a red eye, runny nose, and facial flushing [30].

- Hypnic headache: Hypnic headache is a rare headache that occurs during sleep. It is characterized by a throbbing pain in the head that wakes the person up. Hypnic headaches are more common in older adults and may be caused by a number of factors, such as brain tumors, vascular malformations, and medications [31].

Secondary Headaches: Secondary headaches are headaches that are caused by another underlying medical condition. There are many different types of secondary headaches, each with its own unique set of symptoms and causes.

Some of the most common types of secondary headaches include:

- Sinus headaches: Sinus headaches are caused by inflammation of the sinuses, which are air-filled cavities in the skull. Sinus headaches are often accompanied by other symptoms, such as a stuffy nose, runny nose, and facial pain [32].

- Medication overuse headaches: Medication overuse headaches can occur in people who regularly take over-the-counter or prescription pain relievers for headaches. When people overuse these medications, their headaches can become more frequent and severe [33].

- Rebound headaches: Rebound headaches are a type of medication overuse headache that can occur when people stop taking pain relievers suddenly after using them regularly [34].

- Post-traumatic headaches: Post-traumatic headaches can occur after a head injury. These headaches can be mild or severe, and they can last for a few days or several weeks [35].

- Caffeine withdrawal headaches: Caffeine withdrawal headaches can occur in people who regularly consume caffeine and then stop suddenly [36].

- Exertion headaches: Exertion headaches can occur after strenuous physical activity. These headaches are thought to be caused by increased blood flow to the head [37].

- Hormonal headaches: Hormonal headaches can occur in women at different times during their menstrual cycle, such as during menstruation or ovulation [38].

- Hypertension headaches: Hypertension headaches can occur in people with high blood pressure [39].

Secondary headaches can also be caused by a variety of other medical conditions, such as:

- Brain tumors

- Aneurysms

- Meningitis

- Stroke

- Hydrocephalus

- Temporal arteritis

- Certain medications

Molecular basis of Headache:

The molecular basis of headache is complex and not fully understood, but it is thought to involve a number of different factors, including:

- Neuroinflammation: Neuroinflammation is inflammation of the nervous system. It is thought to play a role in the development of both primary and secondary headaches [40].

- Trigeminal vasodilation: The trigeminal nerve is a major sensory nerve that supplies the head and face. Trigeminal vasodilation occurs when the blood vessels in the trigeminal nerve system widen. This can lead to headache pain [41].

- Cortical spreading depression (CSD): CSD is a wave of depolarization that spreads across the surface of the brain. It is thought to be involved in the development of migraine aura and headache [42].

- Ion channel dysfunction: Ion channels are proteins that regulate the flow of ions into and out of cells. Dysfunction of ion channels in the brain can lead to headaches [43].

- Neurotransmitter imbalances: Neurotransmitters are chemicals that transmit signals between nerve cells. Imbalances in neurotransmitters, such as serotonin and glutamate, can lead to headaches [44].

In addition to these general factors, there are a number of specific molecular mechanisms that have been identified in different types of headaches. For example, in migraine headaches, researchers have identified a number of genes that are associated with increased risk of developing the disorder. These genes are thought to play a role in regulating ion channels, neurotransmitter levels, and other aspects of brain function.

In sinus headaches, inflammation of the sinuses leads to the release of inflammatory mediators, such as histamine and prostaglandins. These mediators can stimulate the trigeminal nerve and cause pain.

In medication overuse headaches, chronic use of pain relievers can lead to changes in the brain that make headaches more likely to occur.

Researchers are continuing to investigate the molecular basis of headache in order to develop new and more effective treatments for this common disorder.

Here are some examples of specific molecular mechanisms that have been identified in different types of headaches:

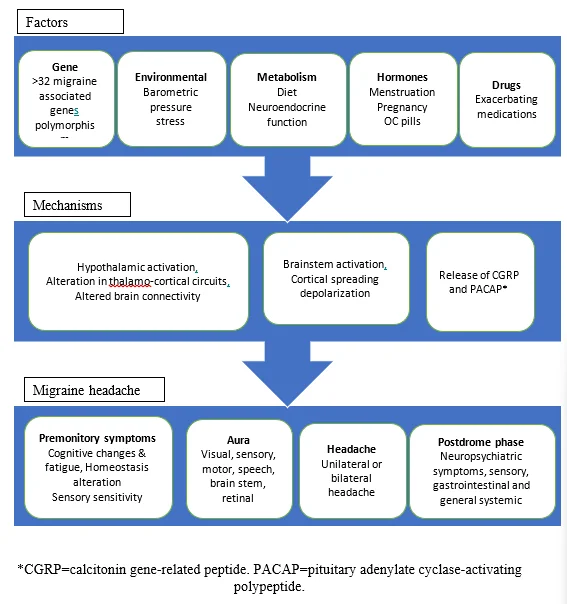

- Migraine headaches: Researchers have identified a number of genes that are associated with increased risk of developing migraine headaches. These genes are thought to play a role in regulating ion channels, neurotransmitter levels, and other aspects of brain function. For example, mutations in the CACNA1A gene, which encodes a calcium channel protein, can cause familial hemiplegic migraine, a rare and severe form of migraine [45]. Figure. 1 showing different risk factors, probable mechanisms and different stages of migraine risk factors.

- Sinus headaches: Inflammation of the sinuses leads to the release of inflammatory mediators, such as histamine and prostaglandins. These mediators can stimulate the trigeminal nerve and cause pain [46].

- Medication overuse headaches: Chronic use of pain relievers can lead to changes in the brain that make headaches more likely to occur. For example, chronic use of acetaminophen can lead to downregulation of the serotonin transporter, which can decrease serotonin levels in the brain. This can lead to headaches, as serotonin is thought to play a role in inhibiting pain signals [47].

8. Therapy for treatment of Headache:

There are a variety of therapies that can be used to treat headaches, depending on the type of headache and its severity.

Prescription pain relievers may be necessary for more severe headaches or headaches that do not respond to over-the counter pain relievers. Prescription pain relievers include acetaminophen (Tylenol), Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB), and naproxen (Aleve) triptans, ergotamine’s (alkaloids), and opioids [48, 49].

Preventive medications may be used to reduce the frequency and severity of headaches. Common preventive medications include beta-blockers, antidepressants, and anticonvulsants [50].

Non-pharmacological therapies can also be used to treat headaches. Common non-pharmacological therapies include:

- Relaxation techniques: Relaxation techniques such as deep breathing, meditation, and progressive muscle relaxation can help to reduce stress and anxiety, which can trigger headaches [51].

- Biofeedback: Biofeedback is a type of therapy that teaches people how to control their bodily functions, such as muscle tension and blood pressure. Biofeedback can be used to reduce headache pain and frequency [52].

- Massage therapy: Massage therapy can help to relax muscles and reduce headache pain [53].

- Acupuncture: Acupuncture is a traditional Chinese medicine practice that involves inserting thin needles into specific points on the body. Acupuncture has been shown to be effective in reducing headache pain and frequency [54].

- Yoga: Yoga therapy as an adjuvant is found to be effective and found to be superior to medical therapy alone in migraine patients [55].

- Neuromodulation techniques: Stimulation of central or peripheral nervous systems by delivering electrical current or magnetic field have sown therapeutic effects on migraine.

Several invasive and noninvasive devices are available like single-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation (sTMS), non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS) such as gammaCore® transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), occipital nerve stimulation, transcutaneous cranial nerve stimulation such as Cefaly® (supraorbital nerve stimulation), sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation, and high cervical spinal cord stimulation. At present the sTMS and Cefaly® have level A evidence, tDCS level B, and nVNS level C [56].

As the treatment of headache comes in the domain of various different specialties other than headache specialist or neurologist a more inclusive or simple working classification were developed which give confidence to other medical professionals like general physicians to provide adequate primary treatment for headache patients [57].

At the end this must be understood that headache is not a disease which is restricted to the head only, this may involve the neck, face, upper neck, eyes and nearby structure. This can also affect the remote organ systems like gastro-intestinal, other neuro-psychiatry and genito-urinary systems. Management of headache must be individualized based on the individual's disease severity, disability, other associated other medical conditions.

Declaration

Competing interests

None

References:

- Ahmed F. Headache disorders: differentiating and managing the common subtypes. Br J Pain. 2012 Aug;6(3):124-32. doi: 10.1177/2049463712459691

- World Health Organisation. World health report. WHO, Geneva, 2001.

- Amiri P, Kazeminasab S, Nejadghaderi SA, Mohammadinasab R, Pourfathi H, Araj-Khodaei M, Sullman MJM, Kolahi AA, Safiri S. Migraine: A Review on Its History, Global Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Comorbidities. Front Neurol. 2022 Feb 23;12:800605. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.800605.

- Goldberg L. D. The cost of migraine and its treatment. The American Journal of Managed Care. 2005:S62–7.

- GBD 2016 Headache Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Nov;17(11):954-976. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30322-3.

- Babateen O, Althobaiti FS, Alhazmi MA, Al-Ghamdi E, Alharbi F, Moffareh AK, Matar FM, Tawakul A, Samkari JA. Association of Migraine Headache With Depression, Anxiety, and Stress in the Population of Makkah City, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus. 2023 May 31;15(5):e39788. doi: 10.7759/cureus.39788.

- Kulkarni GB, Rao GN, Gururaj G, Stovner LJ, Steiner TJ. Headache disorders and public ill-health in India: prevalence estimates in Karnataka State. J Headache Pain. 2015;16:67. doi: 10.1186/s10194-015-0549-x.

- Government of India. 2011 census data. Available at http://censusindia.gov.in/ (last accessed 30 April 2015)

- International Headache Society. "The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-3)." Cephalalgia. 2018; 38(1): 1-211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102417738202.

- Chinthapalli K, Logan AM, Raj R, Nirmalananthan N. Assessment of acute headache in adults - what the general physician needs to know. Clin Med (Lond). 2018 Oct;18(5):422-427. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.18-5-422.

- https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/headache

- Turner DP, Houle TT. Psychological evaluation of a primary headache patient. Pain Manag. 2013 Jan 1;3(1):19-25. doi: 10.2217/pmt.12.77.

- Edvinsson JCA, Viganò A, Alekseeva A, Alieva E, Arruda R, De Luca C, D'Ettore N, Frattale I, Kurnukhina M, Macerola N, Malenkova E, Maiorova M, Novikova A, Řehulka P, Rapaccini V, Roshchina O, Vanderschueren G, Zvaune L, Andreou AP, Haanes KA; European Headache Federation School of Advanced Studies (EHF-SAS). The fifth cranial nerve in headaches. J Headache Pain. 2020 Jun 5;21(1):65. doi: 10.1186/s10194-020-01134-1.

- Shahrokhi M, Asuncion RMD. Neurologic Exam. 2023 Jan 16. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. PMID: 32491521.

- Thulasi P, Fraser CL, Biousse V, Wright DW, Newman NJ, Bruce BB. Nonmydriatic ocular fundus photography among headache patients in an emergency department. Neurology. 2013 Jan 29;80(5):432-7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31827f0f20.

- Almazov I, Brand N. Meningismus is a commonly overlooked finding in tension-type headache in children and adolescents. J Child Neurol. 2006 May;21(5):423-5. doi: 10.1177/08830738060210050601. PMID: 16901450.

- Shin HE, Park JW, Kim YI, Lee KS. Headache Impact Test-6 (HIT-6) scores for migraine patients: Their relation to disability as measured from a headache diary. J Clin Neurol. 2008 Dec;4(4):158-63. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2008.4.4.158.

- Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Dowson AJ, Sawyer J. Development and testing of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) Questionnaire to assess headache-related disability. Neurology. 2001;56(6 Suppl 1):S20-8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.suppl_1.s20.

- Ormseth BH, ElHawary H, Huayllani MT, Weber KD, Blake P, Janis JE. Comparing Migraine Headache Index versus Monthly Migraine Days after Headache Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2024 Jun 1;153(6):1201e-1211e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000010800. Epub 2023 Jun 6. PMID: 37285213.

- Aicher B, Peil H, Peil B, Diener HC. Pain measurement: Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and Verbal Rating Scale (VRS) in clinical trials with OTC analgesics in headache. Cephalalgia. 2012 Feb;32(3):185-97. doi: 10.1177/03331024111430856. PMID: 22332207.

- Shibata M, Nakamura T, Ozeki A, Ueda K, Nichols RM. Migraine-Specific Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (MSQ) Version 2.1 Score Improvement in Japanese Patients with Episodic Migraine by Galcanezumab Treatment: Japan Phase 2 Study. J Pain Res. 2020 Dec 31;13:3531-3538. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S287781. PMID: 33408512; PMCID: PMC7781358.

- Ravishankar K. The art of history-taking in a headache patient. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2012 Aug;15(Suppl 1):S7-S14. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.99989. PMID: 23024567; PMCID: PMC3444228.

- Holle D, Obermann M. The role of neuroimaging in the diagnosis of headache disorders. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2013 Nov;6(6):369-74. doi: 10.1177/1756285613489765. PMID: 24228072; PMCID: PMC3825114.

- Kennis K, Kernick D, O'Flynn N. Diagnosis and management of headaches in young people and adults: NICE guideline. Br J Gen Pract. 2013 Aug;63(613):443-5. doi: 10.3399/bjgp13X670895. PMID: 23972191; PMCID: PMC3722827.

- Robbins MS. Diagnosis and Management of Headache: A Review. JAMA. 2021 May 11;325(18):1874-1885. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.1640. PMID: 33974014.

- Chowdhury D. Tension type headache. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2012 Aug;15(Suppl 1):S83-8. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.100023. PMID: 23024570; PMCID: PMC3444224.

- Hargreaves R. New migraine and pain research. Headache. 2007 Apr;47 Suppl 1:S26-43. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00675.x. PMID: 17425708.

- Kandel SA, Mandiga P. Cluster Headache. 2023 Jul 4. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. PMID: 31334961.

- Gelfand AA, Robbins MS, Szperka CL. New Daily Persistent Headache-A Start With an Uncertain End. JAMA Neurol. 2022 Aug 1;79(8):733-734. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.1727. PMID: 35788252; PMCID: PMC10084815.

- Hameed S, Sharman T. Hemicrania Continua. 2024 Jul 27. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. PMID: 32491500.

- Al Khalili Y, Chopra P. Hypnic Headache. 2023 Apr 10. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. PMID: 32491530.

- Maurya A, Qureshi S, Jadia S, Maurya M. "Sinus Headache": Diagnosis and Dilemma?? An Analytical and Prospective Study. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019 Sep;71(3):367-370. doi: 10.1007/s12070-019-01603-3. Epub 2019 Jan 19. PMID: 31559205; PMCID: PMC6737117.

- Fischer MA, Jan A. Medication-Overuse Headache. 2023 Aug 22. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. PMID: 30844177.

- Aleksenko D, Maini K, Sánchez-Manso JC. Headache From Medication Overuse. 2023 Jun 26. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. PMID: 29262094.

- Defrin R. Chronic post-traumatic headache: clinical findings and possible mechanisms. J Man Manip Ther. 2014 Feb;22(1):36-44. doi: 10.1179/2042618613Y.0000000053. PMID: 24976746; PMCID: PMC4062350.

- Alstadhaug KB, Ofte HK, Müller KI, Andreou AP. Sudden Caffeine Withdrawal Triggers Migraine-A Randomized Controlled Trial. Front Neurol. 2020 Sep 10;11:1002. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.01002. PMID: 33013662; PMCID: PMC7512113.

- National Headache Foundation. Exertional Headaches (https://headaches.org/2007/10/25/exertional-headaches/). Accessed 11/17/2021.

- https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/hormone-headaches/

- Assarzadegan F, Asadollahi M, Hesami O, Aryani O, Mansouri B, Beladi Moghadam N. Secondary headaches attributed to arterial hypertension. Iran J Neurol. 2013;12(3):106-10. PMID: 24250915; PMCID: PMC3829292.

- DiSabato DJ, Quan N, Godbout JP. Neuroinflammation: the devil is in the details. J Neurochem. 2016 Oct;139 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):136-153. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13607. Epub 2016 May 4. PMID: 26990767; PMCID: PMC5025335.

- White TG, Powell K, Shah KA, Woo HH, Narayan RK, Li C. Trigeminal Nerve Control of Cerebral Blood Flow: A Brief Review. Front Neurosci. 2021 Apr 13;15:649910. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.649910. PMID: 33927590; PMCID: PMC8076561.

- Lauritzen M, Dreier JP, Fabricius M, Hartings JA, Graf R, Strong AJ. Clinical relevance of cortical spreading depression in neurological disorders: migraine, malignant stroke, subarachnoid and intracranial hemorrhage, and traumatic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011 Jan;31(1):17-35. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.191. Epub 2010 Nov 3. PMID: 21045864; PMCID: PMC3049472.

- Eren-Koçak E, Dalkara T. Ion Channel Dysfunction and Neuroinflammation in Migraine and Depression. Front Pharmacol. 2021 Nov 10;12:777607. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.777607. PMID: 34858192; PMCID: PMC8631474.

- Teleanu RI, Niculescu AG, Roza E, Vladâcenco O, Grumezescu AM, Teleanu DM. Neurotransmitters-Key Factors in Neurological and Neurodegenerative Disorders of the Central Nervous System. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 May 25;23(11):5954. doi: 10.3390/ijms23115954. PMID: 35682631; PMCID: PMC9180936.

- Grieco GS, Gagliardi S, Ricca I, Pansarasa O, Neri M, Gualandi F, Nappi G, Ferlini A, Cereda C. New CACNA1A deletions are associated to migraine phenotypes. J Headache Pain. 2018 Aug 30;19(1):75. doi: 10.1186/s10194-018-0891-x. PMID: 30167989; PMCID: PMC6117225.

- Watts AM, Cripps AW, West NP, Cox AJ. Modulation of Allergic Inflammation in the Nasal Mucosa of Allergic Rhinitis Sufferers With Topical Pharmaceutical Agents. Front Pharmacol. 2019 Mar 29;10:294. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00294. PMID: 31001114; PMCID: PMC6455085.

- Carlsen LN, Munksgaard SB, Nielsen M, Engelstoft IMS, Westergaard ML, Bendtsen L, Jensen RH. Comparison of 3 Treatment Strategies for Medication Overuse Headache: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol. 2020 Sep 1;77(9):1069-1078. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1179. PMID: 32453406; PMCID: PMC7251504.

- D'Amico D, Tepper SJ. Prophylaxis of migraine: general principles and patient acceptance. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008 Dec;4(6):1155-67. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s3497. PMID: 19337456; PMCID: PMC2646645.

- Queremel Milani DA, Davis DD. Pain Management Medications. 2023 Jul 3. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. PMID: 32809527.

- Silberstein SD. Preventive Migraine Treatment. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2015 Aug;21(4 Headache):973-89. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000199. PMID: 26252585; PMCID: PMC4640499.

- Norelli SK, Long A, Krepps JM. Relaxation Techniques. 2023 Aug 28. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. PMID: 30020610.

- Ingvaldsen SH, Tronvik E, Brenner E, Winnberg I, Olsen A, Gravdahl GB, Stubberud A. A Biofeedback App for Migraine: Development and Usability Study. JMIR Form Res. 2021 Jul 28;5(7):e23229. doi: 10.2196/23229. PMID: 34319243; PMCID: PMC8367148.

- Quinn C, Chandler C, Moraska A. Massage therapy and frequency of chronic tension headaches. Am J Public Health. 2002 Oct;92(10):1657-61. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.10.1657. PMID: 12356617; PMCID: PMC1447303.

- Molsberger A. The role of acupuncture in the treatment of migraine. CMAJ. 2012 Mar 6;184(4):391-2. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.112032. Epub 2012 Jan 9. PMID: 22231676; PMCID: PMC3291665.

- Kumar A, Bhatia R, Sharma G, Dhanlika D, Vishnubhatla S, Singh RK, Dash D, Tripathi M, Srivastava MVP. Effect of yoga as add-on therapy in migraine (CONTAIN): A randomized clinical trial. Neurology. 2020 May 26;94(21):e2203-e2212. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009473. Epub 2020 May 6. PMID: 32376640.

- Schoenen J, Roberta B, Magis D, Coppola G. Noninvasive neurostimulation methods for migraine therapy: The available evidence. Cephalalgia. 2016 Oct;36(12):1170-1180. doi: 10.1177/0333102416636022. Epub 2016 Jul 11. PMID: 27026674.

- Thomas P, Kumar A, Subir A, McGeeney BE, Raje M, Garg D, Aroor CD, Elavarasi A, Castle K. Classification of Head, Neck, and Face Pains First Edition (WHS-MCH1): Position paper of the WHS Classification Committee. Headache Medicine Connections. 2021:1(1): 1–108. https://doi.org/10.52828/hmc.v1i1.classifications

No. of Figure: 1

Figure.1: Shows various triggers, mechanisms and clinical features of migraine.